I am not my hair...I think: Black Girl "alien-ness" and Natural hair

Can a girl just be pretty?

“Eventually I knew precisely what hair wanted: it wanted to grow, to be itself, to attract lint, if that was its destiny, but to be left alone by anyone, including me, who did not love it as it was…The ceiling at the top of my brain lifted; once again my mind (and spirit) could get outside myself. I would not be stuck in restless stillness, but would continue to grow.”

-Alice Walker, “Oppressed Hair Puts a Ceiling on the Brain”

In 2017 I was born again. Under the heat of florescent lights, I snipped away a lifetime of dead hair. As the hair collected in my dorm’s bathroom sink, I smiled. I’m free, I thought rebelliously. No more flat irons. No more silk presses every two weeks. No more dodging humidity. Instead, I became an official student of Youtube University, and my curriculum consisted of natural hair content.

8:30 am - Wash n go tutorial for 3c/4a

12:15 pm - Two strand twists for beginners

3:30 pm - How to get a bouncy perm-rod set

4:50 pm - Do’s and Don’ts for growing Type 4 hair

6:20 pm - How to grow your natural hair in 3 months

The class list had me hooked. Soon, my weekly schedule and newfound identity transitioned into experimenting with hairstyles. From perm rod sets to defined wash n go’s, I was sifting through my coil journey, desperate to make myself beautiful. Little did I know, my big chop wasn’t just a curly cut: it was an unmasking. The brave unmasking, though liberating, led to a new cage. One where my hair told people stories about me before they attempted to even speak to me.

Fate of the Fro-ism

As a mega-nerd for science-fiction and speculative fantasy, I found a delightful link between inhuman suffering and my natural hair journey. Where there’s cursed Orcs in Mordor, there’s a girl in Atlanta suffering at the hands of a leave-in conditioner that didn’t properly moisturize her hair. Where there’s thousands of fae-races with different powers, there’s combinations of hair types and porosities. These comparisons shielded me from feeling ridiculous when family members asked the last time I combed my hair. I’m a faerie, I’d keep telling myself. This fantastical identifier urged me to continue as a naturalista, while also reclaiming my confidence.

Combined with healthy doses of stoicism, the link of fantasy and Blackness led to my radical acceptance. I understood I wouldn't reach inner-joy by learning how to flat-twist or achieving the best fro in the room. Contentment would have to pull from a place of no return: acceptance of fate. Every fantasy lover knows an integral part of tragic heroes and villains is a nasty order of fate. The doom of eternal suffering extends beyond the physical entrapment; it’s also the mental. It’s the leathery twine connecting can I actually do this? with what am I so afraid of?

Before I dive into texturism, I want to first touch on my alien-ness. Well, our alien-ness as Black women. The alien metaphor works in tandem with Afrofuturistic techniques to connect Black living experiences with that of science-fiction. Aside from the technologically advanced Wakanda, Afrofuturism is utilized by several Black scholars to discuss race, gender, identity, sexuality, etc.

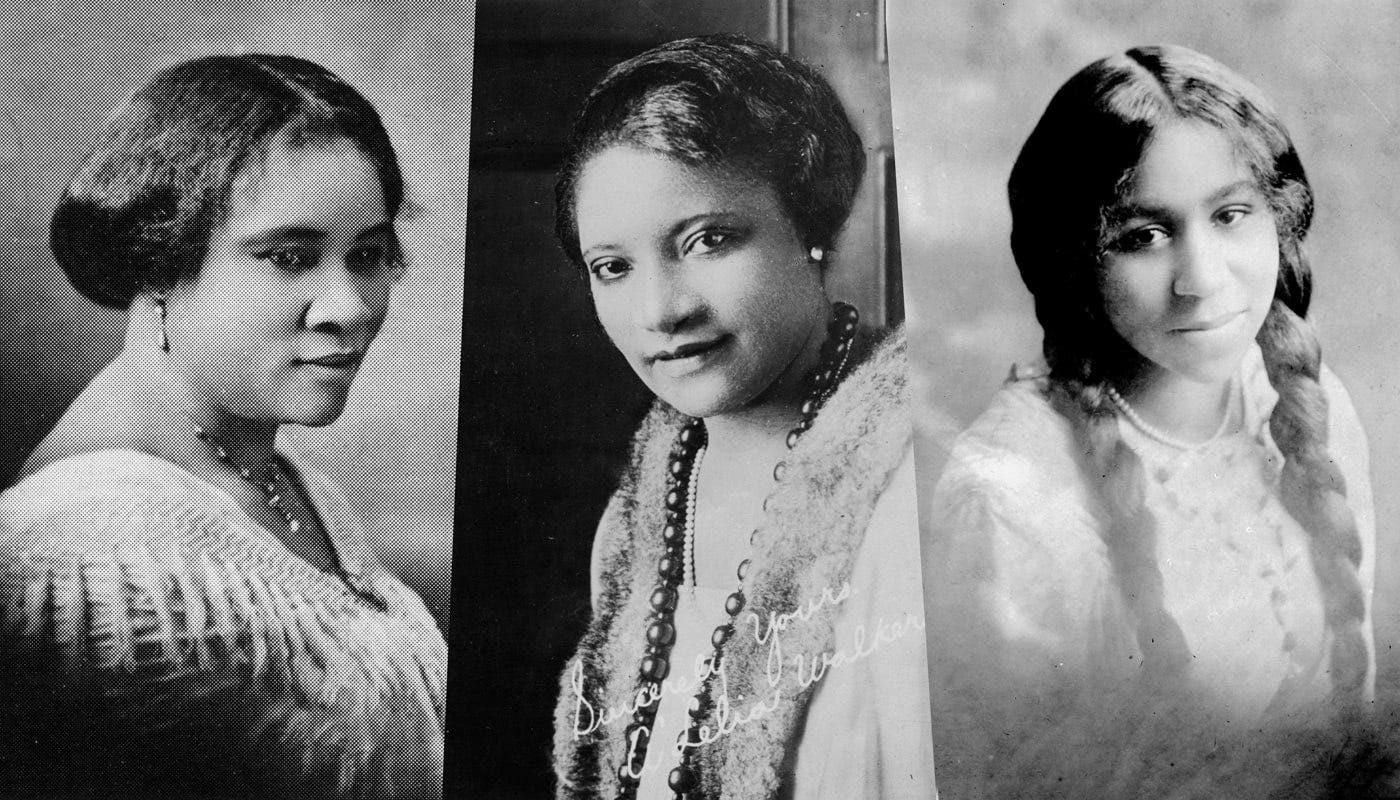

Ytasha L. Womack’s Afrofuturism: The World of Black Sci-fi and Fantasy Culture beautifully connects Afrofuturistic themes of identity with Black double consciousness, and alien-ness. Through the science-fiction lens, Black writers can wrestle with their “alien” fate on earth. Like extraterrestrials, we’re historically studied, probed, feared, replicated, and forever misunderstood. Since emancipation, African-Americans used our alienation to birth a culture from the ground up. As we grappled with our new identities and freedoms, we blossomed into teachers, business owners, activists, and artists — all while dealing with racial violence. Continuous subjugation further pushed Black Americans to cope through creation, thus resulting in several powerful movements. Education. Art. Beauty. Our innovation always found ways to represent our ingenious creativity and refusal to accept damnation. One of these movements, the natural hair movement, is an excellent representation of our perseverance.

As a potent example of Black power and radicalism, the natural hair movement has transformed over the years by highlighting our resilience and communal conflict.

“Improvisation, adaptability, and imagination are the core components of this resistance and are evident both in the arts and Black cultures at large. Jazz, hip-hop, and blues are artistic examples, but there are ways of life that are based on improvisation, too, that aren’t fully understood.”

-Ytasha L. Womack, Afrofuturism: The World of Black Sci-fi and Fantasy Culture

The Motherships’ protection

Beyond Black resistance and picked out fros, Black girl hair is rooted in scrutiny. Black girl hair, in all its kinky-coily glory, is too alien for white America. So, if Black girls were to fit in, we’d need to tame our manes.

Dating around four-years-old, precisely when little Black girls sport twin puffs with colorful bows, our mothers began the rearing. Though saddening, the rearing is protection against the curse of ugly. Ugly in fantasy — think trolls in The Hobbit — maims you undesirable. When one is undesirable, one doesn’t get hired…or married. One does not survive. Even if we’re free to choose our paths, generational survival has taught Black women to uphold safety through marriage and respectability politics. To protect her little girl, the Black mother insists on teaching “prettification”.

“In fantasy, the exterior determines how one will be received. We see this in Elves vs Orcs, or “evil” stepmothers vs saint stepdaughters; goodness is ethereally clean, and evil is dark and unwanted. For Black women, history marked us eternally “dark” and “unwanted", which justifies violence and subjugation. To avoid this, prettification promises better experiences (career, romance, safety, etc). Like respectability politics, prettification is rooted in misogyny, as it also requires Black women to rely on male acceptance.”

-Adia Ayanna, “I Am Not My Hair…I Think: Black Girl “alien-ness” and Natural Hair”

Black American women’s appearance extends beyond smooth edges and ironed blouses — it’s our armor.

In order for the armor to stick, Black mother’s are persistent with grooming and white lies: “no one likes girls with hair like that” “you don’t look your best with that hair”. These lies aren’t adamantly spoken like morning prayers, but whispered through routine relaxers and praising “good hair”.

Despite the risk of damaged hair and uterine cancer, the alien Black girl chases this perfection to the ends of earth. Beneath the rigorous routine of silk pressing and lace-frontin’, there lies a desire to coast into the ease of beauty.

But natural hair is a beast of its own land. Behind the proclamation of embracing Black beauty, freedom, and empowerment, there’s the ugly root of texturism. It spawns side-eyeing from older family members, uninvited petting from non-Black hands, and crippling insecurity.

This alone led me to a new realization: natural hair can be just as toxic as relaxed hair.

Naturals vs Non-Naturals

My new realization reminded me why Prince Nuada felt so passionately against humans in Hellboy II: The Golden Army (2008). Faes worked for peace and harmony, but humans brought greed and destruction. Similarly, Black women create beauty trends and innovation for our hair, yet we’re still advised to wear wigs during job interviews. Hellboy and his team protected humans from danger, but were gawked at with disgust from the public. Why would they ever want to conform? Better yet, why would Black women continue to strive for a beauty standard in a society that historically disenfranchised them?

The greatest difference between Prince Nuada’s brash and violent plans compared to Hellboy, is Hellboy didn’t seek the annihilation of humans. He also didn’t seek to be fully accepted. The same extremes exist in the natural hair community: the naturals vs non-naturals. Those who prevail with Black radicalism, and those who reject it.

It turns the question, “why would Black women continue to strive for a beauty standard in a society that historically disenfranchised them” into “why would Black women wear their natural hair if it’s continuously discriminated against by both non-Black AND Black people?”

The demise of the natural hair community is lack of unity. Lack of unity comes from collective desperation and trauma. Because so many of us felt the pressure to assimilate into white beauty, we stripped our hair of relaxers. We reframed our mental space to believe kinky is just as beautiful as straight. Yet, in the presence of Black women who do not believe this, or simply don’t care, our passion quickly turns ugly.

This creates an expectation of natural hair. But if we remember the trauma of hair straightening and the curse of ugliness, how could we expect Black women to willingly embrace their kinky hair? Furthermore, it’s not just texture; it’s products and routine. How do we magically know how to choose the right shampoos and hair styles when wigs and silk presses were our only defense? With the amount of do’s and don’ts for natural hair, it’s sometimes easier to say fuck it and throw the wig on.

“I feel more put together with my hair straight”, “wearing wigs means you hate your hair”, “men don’t like that nappy shit”. The more I read the back and forth under what was supposed to be a helpful twist out video, the more I lose faith. Is there a happy medium where Black women can be just be, regardless of our hair?

If one claims to not “be” of their hair by straightening or relaxing, they’re self-hating. If one claims to be “of” their hair by refusing to straighten their hair, they’re thinking too hard on it. Both cases still result in Black women being othered. Still Alien.

The proverbial “double-consciousness” lives on with our hair. We present to the world — no matter how slick our buns — as Black and othered. In our community, this rejection also appears, regardless if we’re running a pressing comb or pick through our hair.

What if our misunderstood improvisation with our hair isn’t the battle between natural vs non natural? What if the natural hair movement AND lace-fronts are evidence that our “alien-ness” is supposed to be complicated?

A great example is Fantastic Planet (1973) in which two groups of enslaved humans were at a cross roads for liberation. Some believed in educating through their oppressors’ intellectual devices, while others survived on skepticism and violent rituals. Both groups’ liberation tactics were formed under an oppressive regime, meaning both actions are side effects of survival. If Black people, specifically Black women, endured centuries of systemic racism, and currently still deal with that same oppression for our hair, why do we expect one form of resistance?

Radical acceptance of alien-ness, also means radically accepting communal liberation will not happen in one lifetime. It will not look the same for every generation, and it might not be as important for everyone. Online discourse trying to persuade Black women to embrace their natural hair won’t work with fear mongering or shaming. Online discourse spreading misinformation about the difficulty of managing natural hair won’t work either. Rather, radical acceptance begins with self and slowly advocating for others around us. It’s choosing what we believe while understanding the complexities of our history and current landscape. That way, as we strive for liberation, it doesn’t exclude people who don’t fit our preferences.

As we advocate for natural hair and liberation, it’s important for Black women to radically accept this contradictory hair theory and engage with media and books advocating for our unique identities.

Womack cites Reynaldo Anderson’s essay, “Cultural Studies or Critical Afrofuturism: A Case Study in Visual Rhetoric, Sequential Art, and Post-Apocalyptic Black Identity”, to emphasize his theory around “twin-ness as a form of resistance that pulled on Africanisms but also was uniquely formulated for survival” (Womack, 38). Twin-ness includes feminine and masculine qualities (protector/nurturer) to create a balanced community. Not only did the twin-ness help Black women protect their public and private lives, but it also called for several other survival strategies to sustain —Africana womanist or Black feminist epistemologies, queer studies, tonal semantics, etc.

“The point of this alien and post-apocalyptic metaphor, says Anderson, isn’t to get lost in traumas of the past or present day alienation. The alien framework is a framework for understanding and healing.”

Ytasha L. Womack, Afrofuturism: The World of Black Sci-fi and Fantasy Culture

Collective frustration in our presentation is what connects us as Black women. Our shared history of crying over a failed blowout and horror stories of over-charging braiders, is cultural and indicative of relentless perseverance. We’re angry and traumatized from texturism while simultaneously understanding why our mother’s desperately groomed our hair to perfection.

Black hair, whether natural or straight, is still apart of our Afro-American experience — connecting us to years of resistance. Since graduating from Youtube University, I found peace in not being tied to either side. Each time it’s wash day, I return to my nineteen-year-old self who searched for sovereignty in a perm-rod set. To thrive, I abandoned my expectations and allowed life to soften my approach to hair politics. I may not coast fluidly in the beauty margins, but within the alien-ness of my Blackness, I am free to choose my outer appearance as I see fit.

About the blogger: Adia Ayanna is a writer with 8+ years of experience in creative nonfiction and fantasy fiction. Along with an MFA in Writing from Savannah College of Art and Design, Adia has ghostwritten over 40 contemporary romance eBooks. When she’s not binging Sex and the City, Adia loves reading speculative fiction and Celtic mythology.

Interested in reading more? Subscribe today to catch next week’s post!

I found you through TikTok, and I absolutely loved your piece! It inspired me to wear my natural hair more often and embrace it for what it is, rather than trying to manipulate it into something it’s not. I’ve noticed people tend to look at me twice when I wear my natural hair, also adding the fact that I am dark skin. But after reading your work, it makes me want to embrace that even more. Why should I have to change myself or conform to society’s beauty standards just to make others feel comfortable? Why can’t I simply exist as my authentic self? Your piece made me realize that I’ve been lying to myself. I should feel 100% beautiful with my natural, shrunken hair not only when I have a sleek, styled wig, ponytail or braids. You’ve truly opened my eyes and given me a new perspective on how I see my hair and myself. Thank you for helping me embrace my natural beauty with more confidence.

As someone who doesn’t have the same textured hair, I think it’s important that we continue to help others understand, and I think you beautifully work in the Afrofuturism mention!