Monday night I blasted Jimi Hendrix’s “Hey Baby (Rising Sun)”. It’d just finished raining, leaving an indigo tint in the sky. The Atlanta city lights dimmed to an orangey haze, dusting the empty streets in yellow. Jimi’s guitar wailed, filling my apartment with a spiritual tremor. Alabama Shakes “Give Me All Your Love” played next. The tantalizing mixture of Brittany Howard’s soulful voice and electric guitar made the lyrics ecstasy-inducing. Chills splintered down my spine as Howard delivered a guttural note over a minute long guitar break. Drums crashed in like cries from heaven. Moonlight softened the night sky, and my breath became shallow. As time slowed down, my spirit danced in rhythm with the music.

I was at church. And that church was Baptist with a choir crooning about the grace of God’s mysterious presence. The longer I sat on my balcony, letting the The Moody Blues’ “Melancholy Man” take over, I heard God. It wasn’t the God I grew up hearing about in church. It was the God I found the first time I heard Slash’s solo in “November Rain”. God’s voice was glorious, full, and reaping with Blackness.

Summer 2013 I stumbled across a new band. It was the summer I began wearing knee-high combat boots and shopping exclusively at Hot Topic. Already, my closet brimmed with an array of band t-shirts, and my iPod overflowed with dozens of playlists. Metal. Doom Metal. Emo. Classic. Surf Rock. Dreamwave. Dreampop. Green Day. Guns n’ Roses. Muse. Type O Negative. Pierce the Veil. Of Mice and Men. Metallica. Local Natives. The list grew the more I scrolled through Youtube’s sea of artists. I was angsty and rock music remained my only release.

But this new band, autoplayed after Pearl Jam, awakened something new. The vocals were entrancing, the drums angelic, and the guitar outro pure ecstasy. What is this? I asked myself as I furiously typed the band’s name into Google. Suddenly, the veil lifted and I understood why this band felt like home. Fishbone, the band in question, was Black.

When it came to Black rockstars, I only knew Lenny Kravitz and Jimi Hendrix. Admittedly, my introduction to rock was Guns n’ Roses, and I didn’t even realize Slash’s mom was Black until I hit twenty-two. Still, Fishbone’s sound and my lack of knowledge drove me crazy. Long before Fishbone, my attachment to rock music became a huge rift between my parents and I. They couldn’t understood how I found comfort in screaming vocals and shrieking guitar riffs. They also couldn’t understand my collection of band memorabilia and thick, black eyeliner.

Regardless of my profound love with the genre, I was met with the same, tired question anytime someone heard me blasting my music: “Why do you like that white people shit?”

Punk is very activist

I didn’t find the right words for my love of rock until college. As an Africana Studies minor, I took a heap of classes ranging from Black familial issues to Black Feminist Studies. I memorized infamous organizations in the Civil Rights Era, and made good use of my Film Studies major by tapping into Spike Lee and blaxploitation history.

One of my favorite courses, Intro to African American Studies, introduced me to a range of Black activists — Angela Davis, Patricia Hill Collins, Stokley Carmichael, Ida B. Wells, etc. My professor ensured her students knew names outside of Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X. She taught us the names history books didn’t highlight, and the stories of activists who weren’t your conventional college educated, prim protesters. Fannie Lou Hamer, to be exact, was a personal favorite.

Somewhere between learning about activists who lived for their community’s liberation and the haze of guitar solos, I found a link. Black activists and Black rockers understood what it meant to stick the finger to “the man” and advocate for communal freedom. Where Black activism wanted to tear down the system of white capitalist patriarchy, Black rockers ached for a medium to be their raw selves. Black Panthers sported perfectly round fros and leather jackets, whereas Black rockers played with a variety of makeup and punk fashion to represent their vibrancy. Though wildly different in their techniques, activists and rockers shamelessly fought for their individuality in a world that continued to hate them.

This unavoidable link spoke loudly to me the deeper I dove into healing my relationship with my natural hair. I understood my hair represented my blackness, but my love for rock music and alternative fashion was a ticket to expression without fumbling for words. It comforted me when I experienced micro-aggressions, and reminded me there were previous generations of women who had similar visions.

Rock music’s aversion to conforming fed me confidence in ways non-alternative folks couldn’t fathom. So, once I understood that Black punk artists had the same idea as Black activists, I saw Black resistance through fresh eyes. It was a different side to the activism my parents taught me. Rather than biting my tongue and being strategic, I could let wild.

This wildness deepened my love for Fishbone.

Fishbone is recognized as a major part of Black punk and “early pioneers of the 90s’ eclectic ska-fusion/punk-rock sound”, and their lyrics are just as poignant. Their 1993 album “Give a Monkey a Brain and He’ll Swear He’s the Center of the Universe” has a gorgeous range of lyrically-fun songs, as well as pivotal bangers like “Black Flowers”. “Black Flowers” remained on repeat for its nostalgic backing vocals and emotional meaning. The lyrics spoke to a budding part of my own identity:

Black Flowers have lost their way

They've lost their way again

Cursed for their will to dream

Raped by mankind again

Like the auction blocks of castrated dreams

Kills the heart of love turned into disease

And each day I pray

Please take me away

Please take me away

Rarely did I see myself in the lyrics of melancholic punk songs. But “Black Flowers” poetically speaks to Black pain and the misery of remembering our past. Although Fishbone reigns as a memorable LA band, it’s unfortunately not enough to remind other Black folks why rock isn’t just for white folks.

Who gets to rock?

Rock music is often categorized by musty, heavily tattooed white guys with long hair. While Kiss and Nirvana might live up to that name, the origins of rock is blues. And the origins of blues is Black subjugation. Angela Davis’ Blue Legacies and Black Feminism cites blues as a unique way for Black femme blues singers to express their personal lives and sexuality. Blues is categorized as heartfelt and somber with lyrics outlining the horrors of society. When Black folks were being hunted and pushed out of mainstream society, blues became our coping mechanism.

Once blues transitioned into rock n’ roll, and bands like Led Zeppelin took the stage, the blackness and blues aspect of rock took a backseat. It’s undeniable that Zeppelin didn’t learn a thing or two from blues, as Robert Plant’s vocals are exponentially soulful, and the guitar solos colorful; almost like they transcribed the language of my culture.

The main reason I feel Black rockers are confusing in the Black community is because rock isn’t polite. It’s loud and messy. Singers belt into the microphone, raging across the stage. Their bodies are airy, mimicking the energy of the crowd wailing for more. That kind of energetic freedom is often foreign — especially to Black women. Black girls are governed by the eye of scrutiny. Our bodies are too sexual, our hair too grown, and the color red a signal of being “fast-tailed”.

However, modern rock music calls for an abandonment of perfection and rules, and that’s tempting.

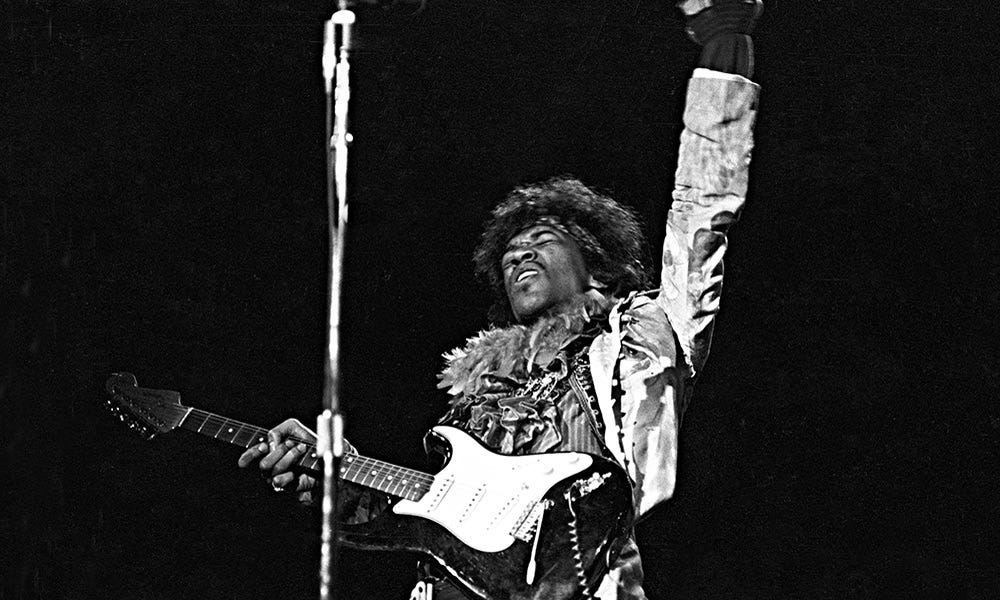

It scrubs the duty of politeness, beckoning for you to forget the tension in your body. It calls for the exuberance of Prince; the fluidity of Grace Jones; the fire of Jimi Hendrix; the stride of Tracey Chapman. It rejects gender roles and appropriate dressing. It’s facial piercings and tattoos of goddesses. It’s less church and more indie shows on the weekends. It’s not caring if my hair is too big and too wild.

Though the rewards of alternative music are endless, it takes a certain dosage of resistance and power to break free from the mold. Our conditioning will tell us, “why are you trying to be like those white girls?” for simply experimenting with our appearance, or daring to face emotional demons through heartfelt lyrics. As a formerly depressed teen who spent a week at an in-patient facility, Pierce the Veil’s “Collide with the Sky” got me through the darkest time in my life. For every Christian therapist reminding me my depression was due to a lack of Jesus, I had a song playing in my head. And those songs formed an unbreakable determination to exist (stubbornly) and unapologetically as myself.

This is the other reason rock music is “too white” for some Black folks.

Mental health is criminally misunderstood in Black kids, and once Black kids migrate towards an unlikeable identity, they’re ridiculed. In my day, “emo” music from bands like Black Veil Brides and Pierce the Veil had sappy lyrics of failed romance or mental frustration. The singers wore their hearts on their sleeves and weren't afraid to smudge their eyeliner. In Black households, rarely was there space to break down and claim you were “depressed” over a relationship. I believe Black kids who understood this found comfort in alt music, as there were so many genres and ways to express mental torment. Recently, depression in Black people is spoken about more openly, but it’s still not expressed as messy. I can barely name a film where a young, Black protagonist is able to unravel and contemplate their mental health without being called weak or “trying to be white”.

Black alternative adults went through a reckoning where they saw the intersection of blackness and alternative-ness, and boldly chose both. In doing so, they chose a never-ending job of ruthlessness. They accept the curse of not fitting into communal boxes and being indescribable to non-black folks. They became pariahs and they’re perfectly okay with that.

I don’t believe that everything tied to Black art is a message of liberation, however I do believe Black art is born from the concept of otherness. Outcasts create questioning. Black outcasts create spaces in rooms we weren’t expected to enter. The Black alternative experience existed long before we picked up a banjo. It started when we resisted enslavement. It grew post-emancipation as African-American culture rose, living on as we became a people decorated with opinions, dreams, and expectations. Music is one of our many cultural languages and it’s eternal. It’s vampiric and haunts nearly every genre — dance breaks in pop, rap verses, Motown, country. It’s the vein in just about every rendition of music and that’s a legacy I’m proud to know.

About the blogger: Adia Ayanna is a writer with 8+ years of experience in creative nonfiction and fantasy fiction. Along with an MFA in Writing from Savannah College of Art and Design, Adia has ghostwritten over 40 contemporary romance eBooks. When she’s not binging Sex and the City, Adia loves reading speculative fiction and Celtic mythology.

Interested in reading more? Subscribe today to catch next week’s post!

It’s so sad that so many people feel this way ! My friends and I grew up listening to this type of music and more especially during tumblr days but no one ever called us white cause I guess we lived in Africa where it’s mostly black people and we’re allowed to have a range of expression. Perhaps there’s a wider issue of white supremacy at hand rather than an unwelcoming black society. Could it be that there’s a way the media and larger society expect black people to present that has made us subconsciously think that we’re pariahs if we listen to different genres of music other than rap or don’t have the ‘baddie’ aesthetic? Lovely piece !

It's a great representation piece for those who are different. Black people are not a monolith, we are as diverse as the deep sea.